Statutory Definition of Domestic Abuse

The Domestic Abuse Act 2021 defines Domestic Abuse as: Behaviour of a person (“A”) towards another person (“B”) is “domestic abuse” if:

A and B are each aged 16 or over and are personally connected to each other, and the behaviour is abusive.

The Act defines abusive behaviour to include:

• Physical or sexual abuse

• Violent or threatening behaviour

• Controlling or coercive behaviour

• Economic abuse

• Psychological, emotional or other abuse

Whether the behaviour consists of a single incident or multiple incidents, it is abuse.

What is Meant by Personally Connected?

The Domestic Abuse Act 2021 makes clear that Domestic Abuse can occur in a wider familial context, as well as between intimate partners.

As defined by the Domestic Abuse Act 2021 two people are “personally connected” to each other if any of the following applies:

• They are, or have been, married or civil partners to each other

• They have agreed to marry one another or entered into a civil partnership agreement (whether or not the agreement has been terminated)

• They are, or have been, in an intimate personal relationship with each other;

• They each have, or there has been a time when they each have had, a parental relationship in relation to the same child

• They are relatives

Section 63 of the Family Law Act says that a person’s relative can be

(a) the father, mother, stepfather, stepmother, son, daughter, stepson, stepdaughter, grandmother, grandfather, grandson or granddaughter of that person or of that person’s spouse, former spouse, civil partner or former civil partner‘ or

(b) the brother, sister, uncle, aunt, niece, nephew or first cousin (whether of the full blood or of the half blood or by marriage or civil partnership) of that person or of that person’s spouse, former spouse, civil partner or former civil partner’.

Section 63 also adds that relatives include ‘in relation to a person who is cohabiting or has cohabited with another person, any person who would fall within paragraph (a) or (b) if the parties were married to each other or were civil partners of each other.’

Children as Victims of Domestic Abuse in their own right

Children are now classed as victims of domestic abuse in their own right under the Domestic Abuse Act 2021 and are no longer seen as ‘passive witnesses’. This recognises the extent of the impact of Domestic Abuse on children. This recognition includes where children see, hear or experience Domestic Abuse within the context of parents or extended family members in line with the definition of personally connected above.

Children and young people experience and use abuse in their own relationships. For those aged over 16, this is now recognised in law. However, we know from research and practice knowledge (locally and nationally) that young people under 16 are also experiencing and using abuse in their relationships.

Prevalence of Domestic Abuse

of children nationally have

experienced Domestic Abuse in the family home before the age

of 18 (NSPCC).

of children living with

domestic abuse experience

direct physical and/or

sexual harm (NSPCC).

of girls by Year 10 had

received hurtful or threatening language from partners

(Plymouth Public Health School’s Survey 2014-2022).

of girls (vs 6% of boys) had

experienced pressure to

have sex or do other sexual things

(Plymouth Public Health School’s Survey 2014-2022).

of girls had been threatened

(vs 7% of men), which is about 1200 – 1500 girls in each year group

(Plymouth Public Health Schools

Survey 2014-2022).

of young women (vs 4%

of men) reported that their

partners didn’t listen to

them even when they said

they didn’t want to do

something sexual.

Each year in Plymouth, there are approximately 580+ children linked to high risk cases discussed at the Multi-Agency Risk Assessment Conference (MARAC).

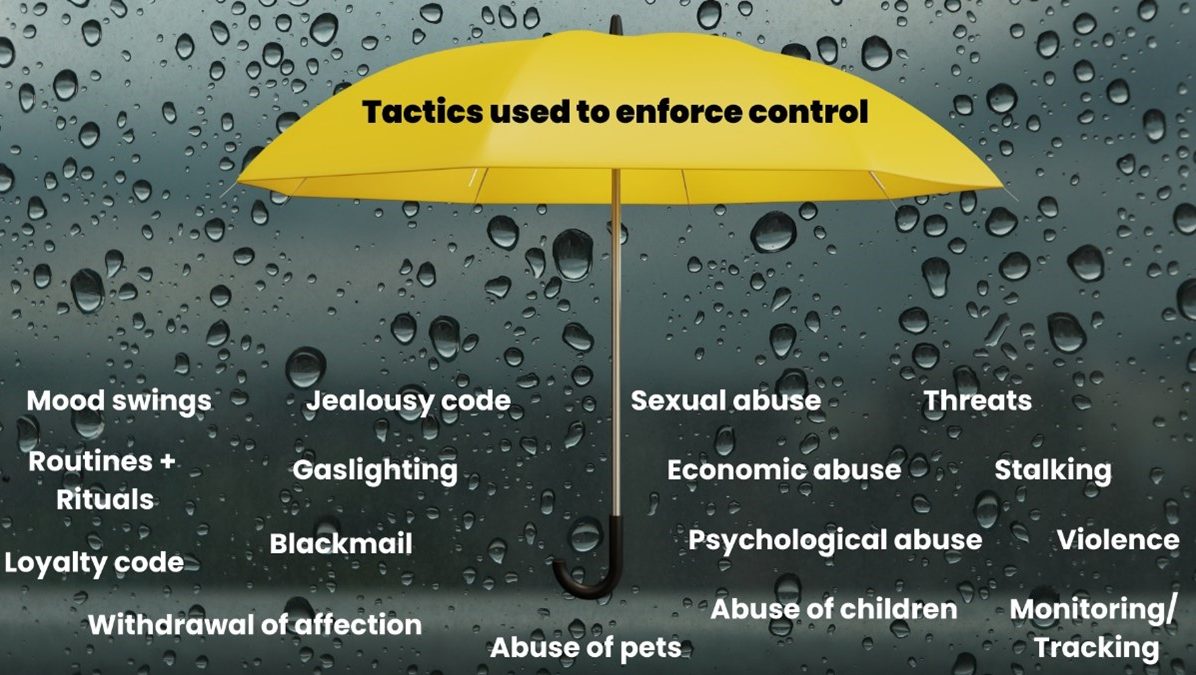

Coercive Control

Understanding coercive control is key to understanding Domestic Abuse as it is the most common framework of Domestic Abuse and the leading cause of Domestic Abuse related deaths (Jane Monkton Smith).

Control is best understood as the goal of Domestic Abuse and people who harm use a range of tactics to enforce control and limit the survivor’s ‘space for action’ (Liz Kelly), limiting the survivor and their children’s ability to freely think, be and do.

People who harm create rules and expectations for the victim/survivor and their children within families and relationships. They enforce these rules using a range of tactics. When these relationship rules and expectations or enforcement tactics are challenged or resisted, the person causing harm will use a range of ‘consequences’ to reinforce control (Jane Monkton Smith).

An example of a ‘rule’ might be ‘you will be loyal’ (loyalty code). The tactics used to enforce this rule might be checking phone, surveillance e.g. cameras or sensors in the home, stalking, and/or making them cut contact with family and friends. The survivor might challenge this by reporting to police, and/or disclosing abuse to a friend or a professional. The consequence then might be silent treatment, counter allegations, child custody threats, hurting pets, hurting children, physical or sexual violence.

It is important to identify and document the rules, tactics of control and consequences as well as the impact on the victim/survivor and children to understand their daily lived experience. Some useful questions to ask are:

• Is this a pattern of behaviour?

• Is this pattern making someone change their daily routines or activities?

• Is this pattern making someone afraid or fearful?

• What would happen if they did/didn’t do this or that?

Over time, due to chronic fear, survivors will modify their behaviour and routines in order to avoid consequences of breaking the relationship’s rules. The ‘what would happen if’ question becomes really important to help you and the victim/survivor and children identify these (often hidden) rules and understand the impact coercive control is having on them.

Post Separation Abuse

Often the person causing harm will escalate or increase their abuse if the victim/survivor and children leave the abusive relationship or family situation or if the person causing harm perceives this to be a risk.

We know from research (Jane Monkton Smith) that separation perceived, threatened or actual, combined with coercive controlling behaviour and physical or sexual violence increases the risk of homicide 900%. There is also an increase in the risk of homicide of children (Women’s Aid).

It is important that when we support survivors, children and young people to leave abusive relationships and family situations that we consider and plan for the potential consequences of this, including increased risk of violence and stalking behaviour. There are also a range of tools, powers and enforcement options available to police, practitioners and victims/survivors to mitigate the risks associated with ending the relationship and to support them to remain in their own home if they wish.